Unas actas secretas, reveladas en un libro que se publicará esta semana, suponen la primera confirmación documental de la capacidad atómica israelí

La posesión de armas nucleares por parte de Israel era hasta ahora un secreto a voces, pero unos documentos revelados por el diario británico The Guardian, en los cuales el ministro de Defensa israelí se ofrece a proporcionar este armamento a la Sudáfrica del apartheid, suponen la primera confirmación documental de la capacidad atómica del Estado hebreo. La política de Israel respecto a su arsenal atómico es de ambigüedad, sin confirmar ni negar su existencia.

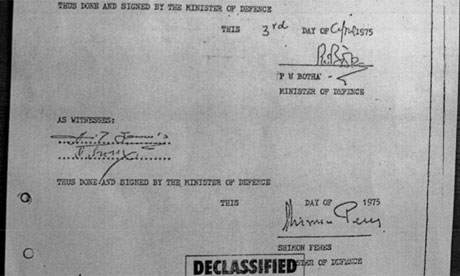

Las actas secretas dan cuenta de las reuniones mantenidas en 1975 entre el entonces ministro de Defensa sudáfricano, Pieter Willem Botha, y su homólogo israelí y actual presidente, Simon Peres. Según los documentos, Peres responde a la petición de cabezas nucleares por parte de Botha ofreciéndoselas "en tres tamaños". Ambos firmaron además un amplio pacto para regir las alianzas militares entre los dos países, con una cláusula que declaraba que "la propia existencia de este acuerdo" debía permanecer secreta.

Los documentos fueron descubiertos por un académico estadounidense, Sasha Polakow-Suransky, durante la investigación para escribir un libro, que saldrá a la venta esta semana en EE UU, acerca de las estrechas relaciones entre Israel y Sudáfrica. Las autoridades israelíes trataron de evitar que el Gobierno sudafricano desclasificara las actas, a petición de Polakow-Suransky.

La revelación cobra especial importancia esta semana, en la que las conversaciones sobre no proliferación nuclear que se celebran en Nueva York se centran en la situación en Oriente Próximo. También echa por tierra la pretensión israelí de presentarse como un país "responsable", que no haría mal uso de sus bombas nucleares.

La colaboración en tecnología militar entre ambos países creció durante los años posteriores. Israel proporcionó a Sudáfrica tritio, un isótopo radiactivo que multiplica la potencia explosiva de las armas termonucleares, mientras que Pretoria suministró sal de uranio, conocido como torta amarilla o yellowcake, que posteriormente se transforma en el uranio enriquecido necesario para fabricar armas nucleares.

Sudáfrica, en pleno aislamiento internacional, quería hacerse con el arma nuclear como fuerza disuasoria ante un posible ataque de un país enemigo. Pero finalmente, no se llevó adelante la compra, en parte por el coste. Además, según The Guardian, la operación tendría que haber contado con el visto bueno del primer ministro israelí, y no es seguro que lo hubiera obtenido. Finalmente, el régimen segregacionista construyó su propia bomba, posiblemente con asistencia de Israel.

http://www.elpais.com/